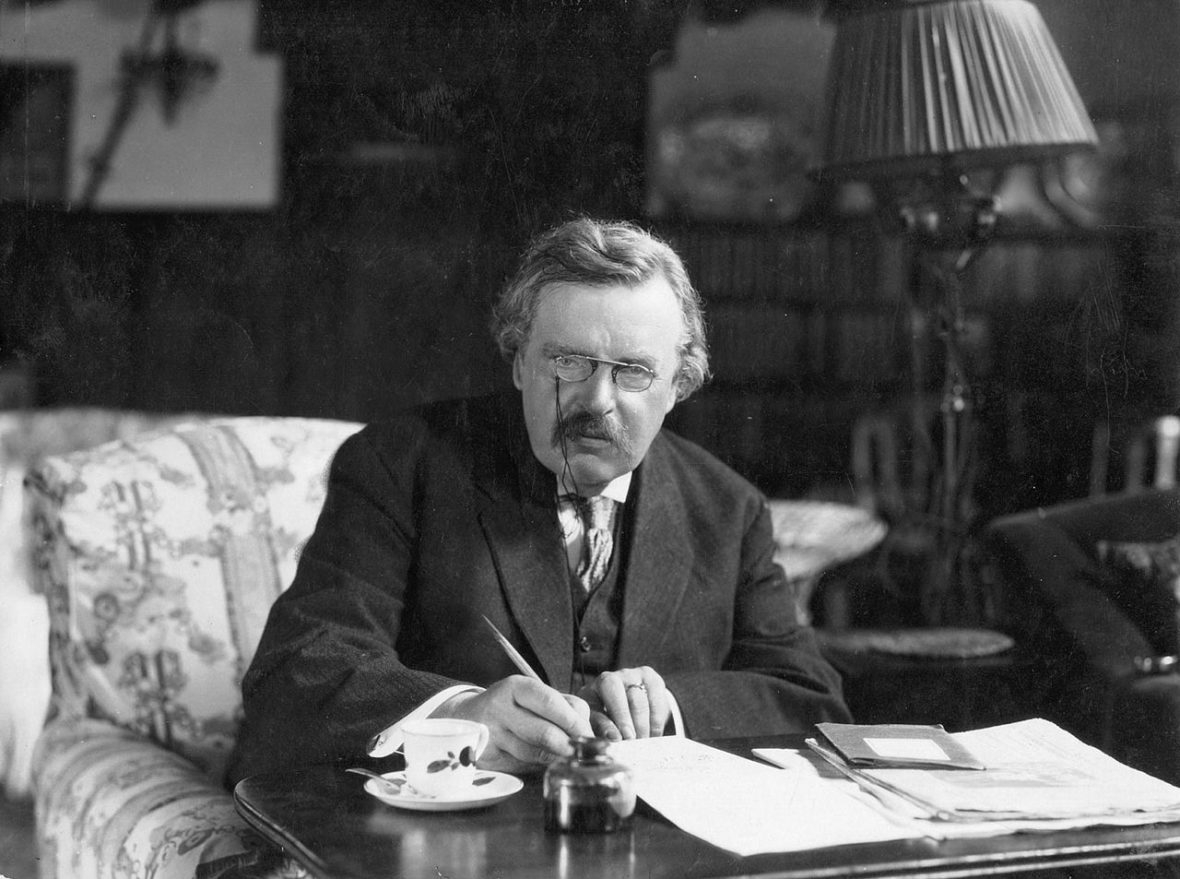

It is commonly known that J.R.R. Tolkien had a role in the conversion to Christianity of the Oxford don and writer C.S. Lewis. However, there was another man who, too, had a hand in the conversion of the great Clive Staples, and his name is Gilbert Keith Chesterton.

While still in the throes of atheism, Lewis made a mistake, in terms of keeping to his atheistic beliefs: he read Chesterton. In his autobiography, Surprised by Joy, Lewis writes:

“In reading Chesterton, as in reading [George] MacDonald, I did not know what I was letting myself in for. A young man who wishes to remain a sound atheist cannot be too careful of his reading. There are traps everywhere — ‘Bibles laid open, millions of surprises,’ as Herbert says, ‘fine nets and stratagems.’ God is, if I may say it, very unscrupulous.”

In the same book Lewis, again, speaks of Chesterton:

“It was here [as an atheist] that I first read a volume of Chesterton’s essays. I had never heard of him and had no idea of what he stood for; nor can I quite understand why he made such an immediate conquest of me. It might have been expected that my pessimism, my atheism, and my hatred of sentiment would have made him to me the least congenial of all authors. It would almost seem that Providence, or some ‘second cause’ of a very obscure kind, quite over-rules our previous tastes when It decides to bring two minds together. Liking an author may be as involuntary and improbable as falling in love. I was by now a sufficiently experienced reader to distinguish liking from agreement. I did not need to accept what Chesterton said in order to enjoy it. His humour was of the kind I like best – not ‘jokes’ imbedded in the page like currants in a cake, still less (what I cannot endure), a general tone of flippancy and jocularity, but the humour which is not in any way separable from the argument but is rather (as Aristotle would say) the ‘bloom’ on dialectic itself.

The sword glitters not because the swordsman set out to make it glitter but because he is fighting for his life and therefore moving it very quickly. For the critics who think Chesterton frivolous or ‘paradoxical’ I have to work hard to feel even pity; sympathy is out of the question. Moreover, strange as it may seem, I liked him for his goodness.”

The glittering sword of Chesterton was his pen.

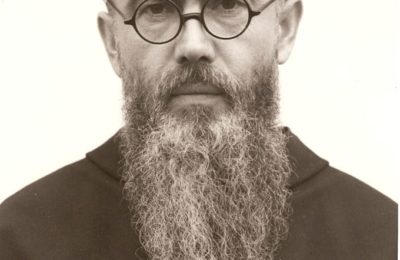

At Chesterton’s death on June 14, 1936, “the then Parish Priest, Monsignor Smith, gave him the last Sacraments …as he lay dying in Top Meadow, Grove Road. Fr Vincent McNabb, O.P., kissed the pen with which he had written so many noble words and sang the Salve Regina, as is the custom in the Dominican Order.” source

Perhaps if there had been no glittering pen of Chesterton, there would have been no glittering pen of C.S. Lewis? We do not know, but for now we can thank both men for developing their art, for telling stories, and expressing their beliefs to us through their pens; and, though we read them separated by many generations, call them our friends.

•SCF