~The following is a re-post from 10/4/18 with edits. SCF

“The transition from the good man to the saint is a sort of revolution; by which one for whom all things illustrate and illuminate God becomes one for whom God illustrates and illuminates all things.”

―

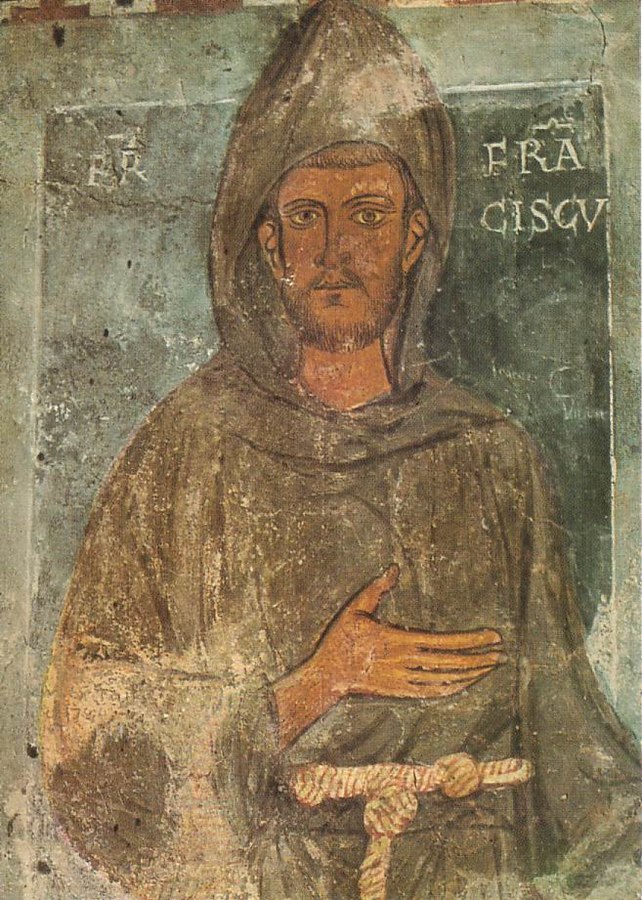

I was writing this morning about St. Francis (b. 1181/1182- d. 1226), who the Church honors today, when I received a phone call from two elves, and their mother, dwelling in a Shire-like Virginian town. This mother reminded me that she had recently heard a homily from a Virginia based diocesan priest regarding this great saint, and noted, in particular, that (paraphrase): the world has recreated St. Francis in its own image, made of him a False Idol, labeled him as a sort of hippie who bounced about lauding nature and the universe; and it was about time we rehabilitate the Knight, the Man, the Saint, who was Brother Francis of Assisi, Italy.

Yes, St. Francis was a Knight, and was raised as a defender and fighter. When he made his famous conversion to God, he did not become less militant; if anything, he became more militant, though not in the militancy of guns and knives, but in an interior militancy that manifests itself in such exterior actions of prayer, mortification, and fasting. He threw off his clothes, and belongings, to follow God in a wholehearted gesture which makes us giving up a Starbucks latte on Tuesdays as an act of reparation seem almost comical.

When we say, St. Francis gave all, we mean, literally, All.

While many men can barely stand a critical word, or an opposing view, and wish to abide in safe spaces, St. Francis went towards conflict: in a famous episode from his life, he traveled to the Sultan, a Muslim, and sought his conversion to the Catholic Faith. He did not say, in the apologetic tones of some post-Vatican II prelates, that all religions are equal. No, he said there was one God, and He created one religion, and a person is to convert to it to be saved. He was courageous in every aspect of living. As Gilbert Keith Chesterton said in his book on this saint, titled, Saint Francis of Assisi:

“It needed ten times more courage to look after a leper than to fight for the crown of Sicily.”

Additionally, with St. Francis:

“The servants of God who had been a besieged garrison became a marching army; the ways of the world were filled as with thunder with the trampling of their feet and far ahead of that ever swelling host went a man singing; as simply he had sung that morning in the winter woods, where he walked alone.” (GKC)

According to both Thomas of Celano and St. Bonaventure (11), St. Francis could not exalt Mary in praise or serve her too much, because it was she who brought our Lord and Savior into our midst and made possible for us direct access to Him. De Maria numquam satis (12). St. Francis is clearly a Marian maximalist, a position clearly bearing on his way of thinking about Mary. If we understand who Mary is, what she has done and continues to do, then we can never exalt her too much, because we cannot come close to matching, let alone exceeding, what the Blessed Trinity has done for her. Of course St. Bonaventure warns against attempting to maximize our Marian prayer and doctrine with stupidities which in fact do not exalt but demean the Virgin Mother of God. But the more we grasp of the mystery objectively, e.g., the Immaculate Conception, the greater must be our praise, devotion and service objectively. For St. Francis, just as the absolute primacy of Christ appears after the triumph of the Cross as Christ’s Kingship over all creation, so the mystery of the Spouse of the Holy Spirit or Immaculate Conception appears as the Queenship of Mary gloriously crowned as Mistress of heaven and earth. In the practical order this constitutes the doctrinal foundation for her universal mediation of grace in the Church and among the Angels, the indispensable basis for realizing the purpose of the Franciscan Order, the rebuilding of the Church: to be without stain or spot, viz., immaculate (13).

These themes converge on the sacrifice of Calvary, hence the importance of perfect conformity to the Crucified through the maternal mediation of Mary in order to accomplish the glorification of the Church. This consists precisely in the completion of the Body of Christ, formed by Mary, so that in and through Christ the Father sees in us what he sees in his Only-begotten Son. This entails on the part of Mary a dual relation: one to Christ as His Mother and so on Calvary Mother of the Church (Virgo Ecclesia facta) and to the Holy Spirit as his instrument in realizing the Incarnation and animating the Church as Body of Christ. Once we see this, we see why Mary is first born daughter of the Father, and how St. Francis’ Marian thought rests profoundly on Trinitarian insights, which underlie the Franciscan thesis on the absolute predestination of Christ and Mary. This Marianized Christology (in St. Maximilian M. Kolbe) will ultimately yield a key to a pneumatology-ecclesiology in the mystery of Mary’s person as Virgin Mother: in relation to the Holy Spirit and in relation to the Church as Virgin-Mother of the faithful (14).

Careful examination of the St. Francis’ Salute to the Virgin (15), whence comes the title Virgo Ecclesia facta, and whose composition is to be related not only to the Portiuncula, St. Mary of the Angels, effectively celebrating Mary’s Assumption and mediation of all graces in the Church, but also to Francis’ conversion experience under the tutelage of the Immaculate Co-redemptrix, particularly reveals how it stresses the joint centrality of the divine Maternity and Incarnation. Thus it reveals how thoroughly the Marian thought of St. Francis was permeated precisely by those three notes stressed by Paul VI in Marialis cultus: the Trinitarian, Christological-pneumatological, and ecclesial (16).

Similarly, the antiphon for the Office of the Passion (17), whence comes the title Sponsa Spiritus Sancti, or Immaculate Conception, whose composition was profoundly linked to the Poverello’s (St. Francis, added by SCF) conversation with the Crucified in San Damiano, the moment when Francis was stigmatized interiorly, reveals the same. This time, however, it does so in relation to the consummation of Christ’s mission on the Cross. The mystery of what is today called the coredemption, based on the “Franciscan thesis,” stands at the very center of this Office and unique antiphon. The identification and labeling of this mystery will be a contribution of the Franciscan Mariological school.

Two doctrinal themes, anchored in the conversion experience of the Poverello (again, St. Francis, added by SCF) in the Church of San Damiano as well demonstrated by Fr. Schneider (18): themes to become central to the Franciscan Mariological School, emerge from this unlimited devotion to Mary as Mother of God: a sense of her unique mediation, first as an active co-cause of the Incarnation and then as spiritual Mother of the Church and its members; and then, as a consequence, a sense of her person as one capable of being the Mother of God and our Mother. For she is Spouse of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin made Church, who is able to bring into this world the Son of God and Savior by the operation of the Holy Spirit, and by the operation of the same Spirit make of the Church virginal Mother of Christ in the minds and hearts of the faithful. Thus, in chapter 10 of his Regula bullata, St. Francis insists that all the friars are obliged to have in themselves “the Spirit of the Lord and his holy operation,” no where so fully realized as in the Mother of God and our Mother.

This sense of Marian mediation of all grace will be a prominent feature of the Christology and Mariology of St. Bonaventure. This sense of her person in St. Francis will later emerge in Duns Scotus’ formulation of the theology of the Immaculate Conception, metaphysical ground of Mary’s universal mediation, as the Incarnation is the ground of Christ’s.

We are not dealing here with two partial aspects of a single mediation, but with a single mediation entire in Christ, but with a Marian mode, for the same reason the mission of the Son involves the mission of the Spirit and divine Maternity. Or mediation in the supernatural order entails a divine and maternal aspect, prefigured in the formation of man as male and female (Gen 2: 18-25) (19): in Bonaventure a dual dimension to a single mediation consummated on Calvary, but ultimately grounded in the dual complementary missions of Word and Spirit (20); and in Scotus founded respectively in the Incarnation and Immaculate Conception. This noted, it is easy to see how the profound insight of St. Maximilian ascribing the same name to the Spirit and Mary (21) is a kind of synthesis of these two great Marian Doctors.

In the Franciscan school, and first of all in St. Francis himself, Christ and Mary are involved, apart from any consideration of sin, in a work of mediation for the rest of the elect. Although from the gnoseological point of view of our theology here and now, demonstration of the Immaculate Conception rests on the prior recognition of our redemption as perfect, ontologically a parte rei the perfection of that redemption derives in fact from the mediation of Christ and Mary: real, even had Adam not sinned (22).

Evidently, the Marian thought of St. Francis, like his profound theology in general, fountainhead of the famed Franciscan school of theology and philosophy (and some would add science), when described in terms of the three possible modes of “our theology” in a time of pilgrimage (23) , is contemplative. For St. Bonaventure, without this form of theology, it would be impossible to perfect or develop the other two, viz., symbolic and academic (or proper). On the other hand without a sound symbolic and academic presentation it would be impossible for the vast majority to grasp the mind of St. Francis and similar saints on the mysteries of faith. source. (and, another source)

That quote was long, but it is instructive, as it details how St. Francis viewed Our Lady, the Immaculate Conception, the Virgin made Church, and how the golden thread of her presence and influence are weaved within (and the thread remains unbroken!) the very foundations of the Franciscan Order.

G.K. Chesterton said about St. Francis, and his relation to Christ and the Blessed Virgin:

“You will not be able rationally to read the Gospel and regard the Crucifixion as an afterthought or an anti-climax or an accident in the life of Christ; it is obviously the point of the story like the point of a sword, the sword that pierced the heart of the Mother of God. And you will not be able rationally to read the story of a man presented as a Mirror of Christ without understanding his final phase as a Man of Sorrows…”

St. Francis was a living Mirror of Christ, he bore the stigmata, he was wedded to the Church. He is a saint that was radically united with Christ, hence with the Mother of Christ. His followers carry on his spirituality and work; they continue to work to bring about the civilization of Love in a fallen world; they keep the golden thread of Marian consecration intact by their dependence on, and consecration to, the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Virgin made Church.

But, what would St. Francis say to us if he could time travel (to us) today?

I think he would say: All is naught if one does not inherit the Kingdom of Heaven. Convert and be saved. Are these not the words of Christ who St. Francis mirrored in such an excellent manner, even to the point of bearing the wounds of Christ, the Stigmata?

G.K. Chesterton also noted that all sorts of men, and women, have followed St. Francis through the years; in varying vocations, occupations, and life circumstances. The vision of St. Francis is not confined simply to the priests, brothers, and sisters of his Order; and, this can be seen in the members of the Third Order (lay members) of St Francis:

“The vision which has been so faintly suggested in these pages has never been confined to monks or even to friars. It has been an inspiration to innumerable crowds of ordinary married men and women; living lives like our own, only entirely different. That morning glory which St. Francis spread over the earth and sky has lingered as a secret sunshine under a multitude of roots and in a multitude of rooms.

In societies like ours nothing is known of such a Franciscan following. Nothing is known of such obscure followers; and if possible less is known of the well-known followers. If we imagine passing us in the street a pageant of the Third Order of St. Francis, the famous figures would surprise us more than the strange ones. For us it would be like the unmasking of some mighty secret society. There rides St. Louis, the great king, lord of the higher justice whose scales hang crooked in favour of the poor. There is Dante crowned with laurel, the poet who in his life of passions sang the praises of Lady Poverty, whose grey garment is lined with purple and all glorious within. All sorts of great names from the most recent and rationalistic centuries would stand revealed; the great Galvani, for instance, the father of all electricity, the magician who has made so many modern systems of stars and sounds. So various a following would alone be enough to prove that St. Francis had no lack of sympathy with normal men, if the whole of his own life did not prove it.”

“So various a following would alone be enough to prove that St. Francis had no lack of sympathy with normal men, if the whole of his own life did not prove it.”

If he could time travel, he would understand our lives, and yet, would still preach the same Gospel, the Good News.

“He was, to the last agonies of asceticism, a Troubadour. He was a Lover. He was a lover of God and he was really and truly a lover of men; possibly a much rarer mystical vocation.” (GKC)

So, today, we thank God for this Knightly Troubadour, who gave his All so that all might be saved; and, we remember him, the man, who gave up house, and family, to follow Christ; the servant who thought himself too lowly to become a priest; the traveler, who went great distances to convert one pagan; and, finally, a man who did not apologize for his beliefs, but became the physical embodiment (in the Holy Stigmata) of his beliefs, in his love of Christ Crucified, a very mysterious happening, and grace.

St. Francis of Assisi, pray for us, pray for the Church you loved with your entire life.

•SCF

~Image: St. Francis, source.

•Marian devotion in the Franciscan Order: link